Fralin Biomedical Research Institute graduate student awarded NIH Fellowship to examine balance, walking in children with cerebral palsy

Cerebral palsy is the most common motor disability in children, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Many children with cerebral palsy have one side of their body weaker than the other side, which impacts mobility, motor skills, and muscle tone. This condition, hemiparesis, results from damage to the developing brain, originating from various conditions including stroke.

Hassan Farah, a Virginia Tech translational biology, medicine, and health (TBMH) graduate student working in the laboratories of Stephanie DeLuca, an associate professor at the Fralin Biomedical Research Institute at VTC, and Robin Queen, an associate professor of biomedical engineering and mechanics in Virginia Tech’s College of Engineering, is studying how children with cerebral palsy balance, walk, and compensate for motor impairments.

Farah was recently awarded $98,000 under the National Institutes of Health’s Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award Individual Predoctoral Fellowship to Promote Diversity in Health-Related Research program to study the limb biomechanics, joint movements, and loading in children with cerebral palsy.

Farah’s doctoral dissertation research blends pediatric rehabilitation and biomedical engineering to ask an important question: How does the anticipation of walking impact balance and the first few steps for children with hemiparetic cerebral palsy?

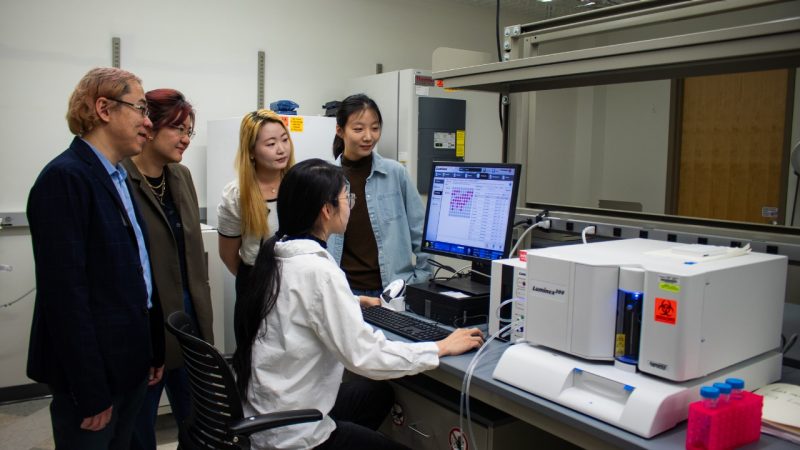

To answer this, the researchers place motion capture sensors to mark different anatomical landmarks, such as a shoulder or hip joint, then they ask children to stand for 35 seconds before walking across the room when they see a light turn on. As the child transitions from standing to walking, 10 3D motion-capture cameras pick up their movements from different angles, while force plates in the floor detect how much weight they press into the ground.

“We’re really focusing on the first three to five seconds of walking – how they initiate that very first step and what strategies they may be using to overcome neuromotor disparities,” Farah said.

Five seconds doesn’t sound like a long time, but Farah said there will be plenty of kinematic data to uncover. By the end of the study, the researchers will have a clearer picture of how children with hemiparesis transfer weight, maintain stability and balance, prepare for walking, the velocity and direction of each motion, and the force applied with each step.

The research team will begin recruiting 40 children between ages 7 and 12 later this year. Half of the participants will have hemiparetic cerebral palsy. The other half, who have not been diagnosed with a motor impairment, will match the participants with hemiparesis in terms of age and sex. This will help the researchers understand any potential changes in biomechanical preparation between children with hemiparesis and their peers.

Farah’s doctoral dissertation project synergizes the research strengths of his two advisors: Queen, who has pioneered novel biomechanics applications in lower extremity orthopedic rehabilitation; and DeLuca, who has developed and implemented clinical interventions to help children with cerebral palsy overcome neuromotor impairments.

Queen and DeLuca both noted that Farah’s enthusiasm and motivation stood out to them.

“He approached me before he was even in the TBMH program and explained his desire to merge rehabilitation and science. His passion and tenacity are what inspired me to become his mentor and help him progress in his career. The rehabilitation field needs enthusiastic young investigators. Hassan is very deserving of this recognition,” said DeLuca, who is also co-director of the Fralin Biomedical Research Institute’s Neuromotor Research Clinic, as well as an associate professor in the Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine’s department of pediatrics and the College of Science’s School of Neuroscience.

“I’ve been interested in working with Dr. Queen since she joined Virginia Tech to harness her lab’s ability to do motion analysis in people with neuromotor impairments,” DeLuca said.

Likewise, Queen also saw the potential to forge a new path in pediatric rehabilitation.

“For years I’ve been engineering frameworks in the orthopedic rehabilitation space, and now we have this unique opportunity to use similar technologies to address new questions in a pediatric population,” said Queen, who also directs the Kevin P. Granata Biomechanics Lab, is an associate professor in the Department of Orthopedic Surgery at the Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine, and a faculty fellow for health data privacy at Virginia Tech. “This collaboration has been years in the making and opens up an exciting future of possibilities.”

DeLuca said their collaborative projects could one day address a critical unmet need for less invasive interventions in cerebral palsy rehabilitation.

“Children with cerebral palsy often have spasticity, and the go-to clinical solution is often surgery,” DeLuca said. “We hope that by understanding the mechanics of walking patterns, we can better define diagnostic categories and one day develop effective interventions as alternatives to surgery.”

Farah earned a bachelor’s degree in health sciences from the University of Arizona. He also serves as the executive chair of the Roanoke Graduate Student Association, and is passionate about mentorship and science advocacy.

“It’s important to me to find ways to act locally to advocate for positive change. I also want to ensure that wherever I am, I’m creating an inclusive environment that allows diverse groups of students, staff, colleagues, and even research participants, to feel valued and empowered by their contributions to science,” Farah said. “This NIH funding will help me achieve my academic and professional goals, and continue to forge an uncharted, interdisciplinary path in health science.”